Trump’s Threat to EV Trucking Rules Undermines Big-Rig Bets

Trump’s Threat to EV Trucking Rules Undermines Big-Rig Bets 2025

Two years ago, Rudy Diaz made a gutsy bet. The 45-year-old owner of Hight Logistics, a trucking company that hauls containers from the bustling ports around Los Angeles, began adding some of the country’s first electric heavy-duty trucks to his fleet.

One rolls by on an overcast morning earlier this month, eerily silent except for its large tires crunching on the asphalt. “There’s no fumes, there’s no noise,” enthuses Diaz, who now boasts 20 electric trucks among his fleet of 75 tractor trailers.

Efforts like Diaz’s were supposed to quickly become the norm for operators of the nation’s heavy-duty fleets, including long-haul truckers traversing multiple states and drayage firms carrying containers from ocean ports.

California enacted a rule in 2020, which has since been adopted by 10 other states, requiring truck makers to sell an increasing portion of emission-free models, including for the largest semi-trucks. California soon followed with another regulation requiring fleet owners to buy more zero-emission trucks. Drayage companies like Hight Logistics faced the most aggressive timeline: They would need to be 100% emission-free by 2035.

Meanwhile, the federal government last year tightened tailpipe requirements for heavy-duty vehicles, which would effectively force truck manufacturers like Daimler Truck AG and Volvo AB to produce dramatically more electric trucks.

Now these rules are teetering. President Donald Trump, who is taking aim at California’s more stringent vehicle requirements, is also expected to go after the federal tailpipe rules. Meanwhile, 19 states, all of which voted for Trump in the most recent election, filed a legal challenge against California’s requirements for truck manufacturers. And in January, the California Air Resources Board effectively gutted its rule that would push fleet owners like Diaz into electric trucks after it became apparent former President Joe Biden wouldn’t grant the required approval before leaving office.

The darkening landscape for such rules is a blow to businesses that have poured gobs of money and years of toil into California’s expected clean-energy transition for heavy-duty trucks.

“It’s a setback,” says Salim Youssefzadeh, the chief executive officer of WattEV, which has spent tens of millions of dollars building charging stations for trucks across California. “That’s probably going to delay some of these larger fleets from going electric.”

It’s also sapping enthusiasm among investors who previously put much-needed capital into these efforts. “We’re much more cautious than we were a year ago, with these changes,” says R. Andrew de Pass, head of renewable and sustainable investments at Vitol Inc., a larger energy trader.

Any slowdown will hinder efforts to clean up one of the economy’s dirtiest sectors. Commercial vehicles are expected to surpass passenger cars as the planet’s leading source of transportation emissions by 2039, according to research firm BloombergNEF. In California, heavy-duty trucks contribute about 7% of the state’s heat-trapping emissions. These trucks run mostly on diesel, which also emits harmful particulates that heighten risks for cancer and asthma near ports and along busy shipping corridors.

The California Air Resources Board, which oversees the state’s clean-truck rules, says it remains committed to slashing pollution from trucks and is considering other courses of action. “We will explore all viable options to reduce harmful emissions…and safeguard our environment,” says a spokesperson for the agency.

Some countries are figuring out how to do this much faster. While there are tens of thousands of small electric delivery vans plying the roads of the US, there were just over 3,000 electric heavy-duty trucks as of the middle of last year, according to CALSTART, a nonprofit focused on clean transportation. China now adds that many every 9 days, thanks to its cheaper batteries and lucrative incentives.

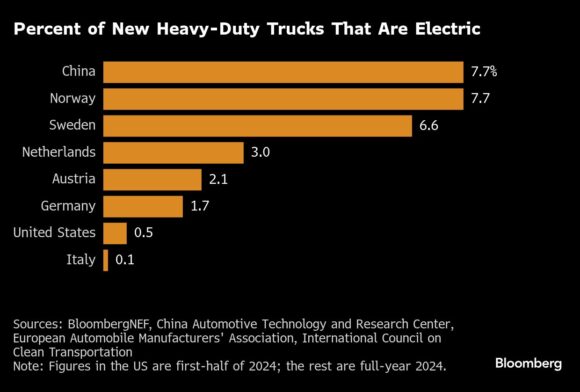

All told, electrics make up about 0.5% of new heavy-duty truck registrations in the US. By contrast, China and Norway have surged past 7%, Sweden topped 6%, the Netherlands reached 3%, and Europe reached 1.4%.

“Policy incentives matter,” says Maynie Yang, a BloombergNEF analyst. By pulling back support at this early stage, the US will stall its development of an EV supply chain and ensure its trucks remain more expensive, she says.

Not all progress in the US relies on stricter mandates. While a new electric truck costs about three times more than a diesel truck in the US, subsidies from California and the ports can cut that extra cost significantly. To help fund these incentives, the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach charge dirtier trucks up to $20 more per load, which electric trucks don’t pay. Diaz, who plans on adding five more EVs this year, estimates his electric trucks will save him a combined $300,000 in such fees this year.

But without government mandates, many fleet operators and policy experts expect electric truck sales in the US will grow at a more plodding pace. And that could end up harming early adopters.

“Without enforcement, I’m competing with guys that have, you know, $50,000 trucks,” says Jim Gillis, who runs the West Coast fleets at IMC Logistics, a large drayage company that has added six electric and 50 hydrogen-powered trucks in the past two years. “It’s tough for me to price myself the right way to compete for business, especially when you have some customers that, frankly, don’t care about the emissions impact that their cargo has.”

The switch to electric trucks hasn’t been easy, even for enthusiasts like Diaz. The first ones he added only go 150 miles on a full battery, while his newer trucks can cover 200 miles. Even then, hotter days or a heavy-footed driver can deplete the battery faster than usual. His trucks have twice run out of juice. “You have to push the limits to see what these trucks can do,” he says.

After much tinkering, Diaz has figured out that the electric trucks can handle about three-quarters of his shipments, including the popular route from the ports to the warehouses scattered around San Bernardino, which is 75 miles inland. He relies on his diesel trucks to handle the longer trips to Bakersfield or Las Vegas.

Charging the trucks is an entirely separate challenge, as they require far more power than an electric sedan. Getting enough electricity to power dozens of trucks often requires the local utility to upgrade its infrastructure, which can cost millions of dollars and take several years.

4 Gen Logistics, for instance, built two charging depots in California to support its 64 electric trucks. The company expected its chargers would take 18 months to install, but, instead, it took three years. Its two locations will eventually require a combined 17 megawatts of power, which is enough for over 10,000 homes.

“It’s like a small city,” says Brad Bayne, vice president at 4 Gen, who estimates the company has paid an extra $9.5 million after incentives to acquire zero-emission trucks, instead of diesel alternatives. “When we first approached SoCal Edison and told them how much power we’d need, they asked us if we were a data center.”

Rudy Diaz says he “struck gold” because a previous tenant in his warehouse had installed an industrial hay baler, which meant there was already plenty of power on hand. But planning when to charge the trucks is a delicate exercise. If they charge overnight or during the morning, when electricity is less expensive, they save about 50% on fuel costs compared to diesel. But topping off a battery during the late afternoon or early evening, when electricity prices are highest, erases all fuel savings.

“This isn’t like a blender where you plug it in and you make a smoothie,” says Diaz. “It’s taken us two years to get ahold of these trucks and learn how to use them.”

Some trucking companies have all but thrown up their hands.

Knight-Swift Transportation Holdings Inc. is a large publicly traded trucking outfit, which generates over $7 billion a year in revenue and operates more than 20,000 heavy-duty trucks. This includes 15 electric long-haul trucks, which it describes as an initial step in its goal to cut greenhouse-gas emissions per mile by half by 2035.

But when an activist investor pressed Knight-Swift last year to set a more ambitious environmental target in line with the Paris Agreement, the company pushed back hard. In an investor filing, they argued this would require a rapid switch to electric trucks, and they skewered the vehicles’ performance. While drayage companies like Hight travel shorter distances, Knight-Swift’s typical route covers almost 500 miles. The electric trucks have delivered a “disappointing” range of about 165 miles, the company wrote, they take a long time to charge, and the trucks weigh at least 6,000-pounds more than a diesel, which means they can’t carry as much cargo.

“We’ve set environmental goals around this, and we were counting on this technology really to be successful,” says Dave Williams, senior vice president of equipment for Knight-Swift, in an interview. But the trucks have limitations that mean carrying less weight shorter distances, he said, which “goes contrary to what our customer demands are today.”

Knight-Swift executives also told Bloomberg Green that electric trucks deliver only a meager 30% climate improvement compared to diesel trucks—a number oft-repeated across the trucking business. A research outfit linked to the trucking industry arrived at that figure by using the national electricity mix from 2019. But the nation’s grid has already become 10% cleaner, and those rapid improvements are expected to continue. In California, where renewable electricity is more ubiquitous, a new electric truck will cut emissions by about two-thirds compared to diesel, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation, a nonprofit think tank. (When asked later for more information about their 30% claim, a Knight-Swift official clarified it isn’t “a hard and fast number,” but one they use “directionally.”)

Some fleets contend they’re fully committed to the new technology. OK Produce, a Fresno, California-based company that hauls salad, avocados, strawberries and other produce, has added 17 electrics to its fleet of about 140 heavy-duty trucks. At first, the new trucks suffered from annoying software glitches, which occasionally knocked them offline. “Admittedly, some of those were pretty tough,” says Brady Matoian, chief executive officer of OK Produce.

But the company has worked through these bugs, and they use the trucks for shorter routes throughout the Central Valley, with each running about 140 miles per day. Many of Matoian’s drivers say they prefer the electrics because they’re powerful and quiet. “They tell me, ‘I leave my job relaxed. I’m not fighting the truck with all the noise,’” he says.

Matoian didn’t know about the mandates when he started researching these trucks – and he says he’ll continue regardless of the government actions. With Fresno suffering some of the worst air quality in the country, he wants to be part of the solution. OK Produce has already installed a massive 10,000-panel solar array across its warehouse roof and parking canopies. Now, cleaning up their fleet is the company’s next logical step, according to Matoian.

“There are all these naysayers who say it won’t work,” he says. “I laugh and say, ‘It did today. I had nine trucks go out today. What do you mean it will never work?’”

Photo: EV trucks at the Hight Logistics trucking facility. Photographer: Alex Welsh/Bloomberg

Copyright 2025 Bloomberg.

Topics

Trucking